Thought on Regionalism and Other Regionality

By Steven Dragonn (Curator, Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Paintings)

As is widely known, the Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Paintings primarily focuses on researching, curating, and exhibiting Chinese paintings, especially those related to the Lingnan School. To the outside world, it is seen as a relatively traditional art museum. Its research and exhibitions revolve around the following main themes: classical Chinese paintings, the 20th-century Lingnan region’s Chinese paintings represented by the Lingnan School, and Lingnan art under the development of New China.

In the summer of 2012, Professor Li JinKun, the director of the Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Painting, curated the “Century of Great Talent: Li Xiongcai Survey Exhibition” at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, which achieved significant success. Around that time, he proposed an idea: to create a space and opportunity for young artists to create and showcase their work during the summer vacation. For a long time, due to administrative constraints, the memorial hall, like the art museum of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, remained closed during summer and winter vacations.

Director Li envisioned using this downtime to interact with the broader art community under the banner of an academic institution. This approach aimed to generate new possibilities for the memorial hall, creating new themes and directions beyond its established focus on mature research. At the outset, I found this concept very appealing, as it brought contemporary art research into the Lingnan region’s academic framework. However, implementing this idea came with challenges, as young artists primarily focus on contemporary art, including forms like installations, paintings, videos, and even multimedia works with light and sound, which incorporate advanced technology. These forms significantly differ from the traditional Chinese paintings the hall’s glass cabinets were designed to showcase.

If we were to display contemporary art forms beyond Chinese paintings, would there be conflicts between the exhibition methods and the works themselves? To address this, we temporarily remodeled the hall, transforming the exhibition area to better meet the needs of contemporary art presentations. Director Li invited young artists Xiao Shanshan, who studied in France, and Yang Yifei, instructor from the Experimental Art Department of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, to discuss how to adapt the space for showcasing experimental art.

Subsequently, we invited Professor Zhou Yong from the Chinese Painting Academy of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts—a prominent figure in contemporary experimental ink painting and post-Lingnanist—to act as the chief curator. Beginning in November 2012, we collected information on outstanding young artists from Guangzhou and surrounding areas, even beyond the Lingnan region. Over six months, we engaged in discussions, artist visits, expert consultations, proposals, theme selection, and space modification plans, then finalizing the exhibition plan by mid-May 2013.

The process, while not exceedingly long, was quite complex. From the creation of the artworks to deliberations about exhibition spaces, the curatorial team expended significant effort to ensure the best possible visual effects and exhibition experience within the constraints of limited funding.

In terms of the exhibition format, the planning team sought to break free from the common pitfalls of “random grouping” and “cliquishness” that have plagued many contemporary art collectives’ exhibitions in Guangzhou and surrounding regions in recent years. The curatorial group collaborated with the director and curator to define the thematic direction of the exhibition. From this starting point, we visited local and regionally connected young artists, assessing their creative practices. We either selected recent works or invited artists to create new pieces based on the thematic framework, tailored to the allocated space.

This approach, while appearing to some as a “cage-like” form of liberalism, was in fact a result of extensive negotiation and coordination among the organizers, curators, and venue managers. While this methodology may draw criticism from those advocating for “theory-first” approaches in curation, I believe the detailed documentation we plan to publish will demonstrate that the artists were not unduly restricted; rather, they were afforded significant creative autonomy.

This freedom was made possible because the organizers granted the curatorial team maximum independence while ensuring artists had equal opportunities for dialogue—a rare gesture in an otherwise hierarchical academic system. This approach highlighted a spirit of “academic freedom,” which was both commendable and crucial.

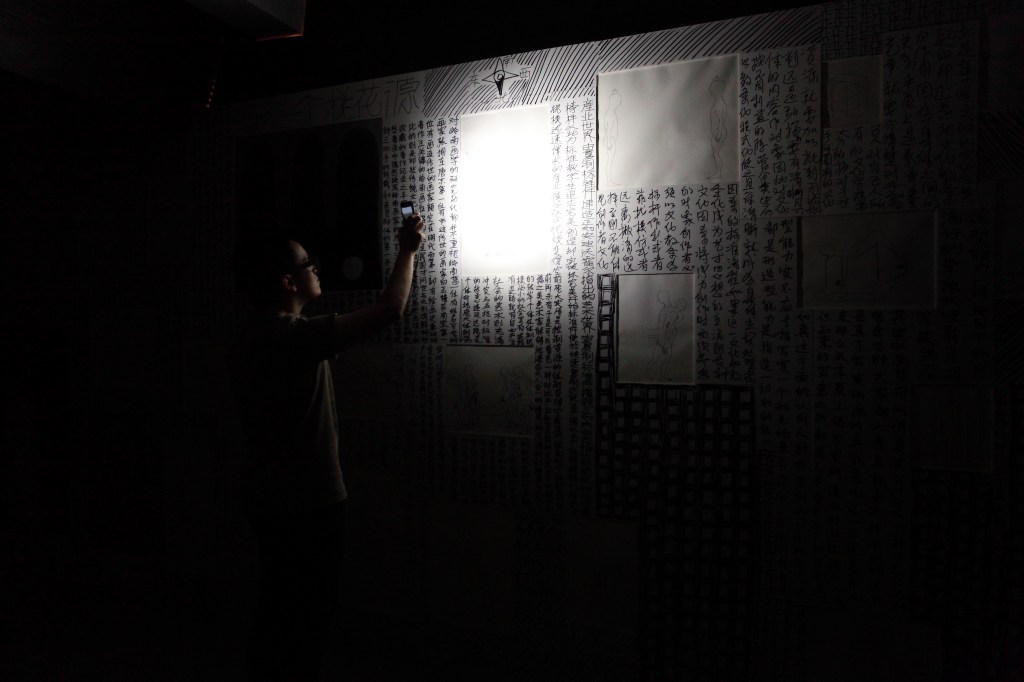

The exhibition lasted two and a half months, spanning the summer vacation and the first two weeks of the new academic term. Due to constraints in scheduling, space remodeling, and installation, a groundbreaking three-week preview period was introduced. In opposite, the official exhibition ran for just nine days. During the preview period, artists could freely adjust their works in consultation with the curatorial team. Some pieces were even created on-site during the preview. While this process resembled a residency program, it was also a deliberate decision by the curators to guide the artists’ creative methods.

By observing and reflecting on the work of their peers in the same exhibition space, the artists engaged in a dynamic exchange that influenced their creations. This mutual interaction aligned with the essence of regionalism: interrelationships and reciprocal influences. This exhibition employed what some scholars might call the “most cumbersome” curatorial approach, requiring tremendous effort and energy from the curatorial team. However, this “cumbersomeness” embodied the most fundamental exploration of the philosophical core of regionalism. Whether or not the desired answers were achieved, the transformations and meanings generated by the process warrant thorough examination.

As curator Zhou Yong remarked, in the process of reflecting and self-discovery, we raise questions like “What is regionalism?” “Who am I?” “What is my living environment?” At the same time, can we also question, “Is my perception of Lingnan the true Lingnan?” “Does the fixed representation of Lingnan’s regional characteristics allow for another form of regionalism?”

The themes are ambitious but not aimlessly broad. The Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Paintings inherently represents a framework of regionalism. As the first attempt to integrate experimental art into the Memorial Hall, starting from discussions of “self” or “self-origin” was the most suitable point of departure. The works presented in the exhibition metaphorically echoed the Big Bang: an explosive collision at a nucleus that radiated outward into diverse directions.

The curatorial team did not initially seek to suppress the possibility of diversification, even at the risk of the exhibition being perceived as a “hodgepodge.” They aimed to use categorization methods to structure the narrative of the exhibited works. However, due to the synchronous processes of creation, display adjustments, and space reconfigurations, it was impossible to derive a coherent “theoretical” or “textual” narrative to guide the audience. Despite this, the final presentation did not devolve into visual chaos. Instead, it prioritized visual appeal, inviting viewers to reflect on the exhibition’s central question: “What is another form of regionalism?”

This visual appeal was consciously imbued with spatial metaphors rooted in the keywords “Lingnan School” and “memorial hall.” Consequently, the theme of “environment as regionalism” became self-evident.

Curating a group exhibition involves envisioning “where it will go” from the start and capturing the set endpoint—the opening moment. Regardless of whether the result aligns with the initial vision, for a curator, the process is a high-risk “experiment.” The core members of the curatorial team—led by Zhou Yong, including myself, Xiao Shanshan, and Yang Yifei—are all artists rather than professional art critics. This dual role is undoubtedly awkward in professional curatorial scene.

For artist-curators, the labor and intellectual effort invested in curating a group exhibition often rival those of creating a significant individual art piece. The key difference lies in the curatorial responsibility to coordinate and balance multiple opinions while preserving as much of the artists’ ideas as possible. As a result, “compromise” becomes the most notable outcome of this curatorial experiment.

In essence, this echoes the Lingnan School’s century-old mission of integrating Eastern and Western artistic perspectives—a groundbreaking concept at the time—while responding to social and practical needs. From this perspective, whether it is perceived as “playing with words” or seen as “truth tested through practice,” the Memorial Hall’s engagement with contemporary experimental art undeniably holds substantive academic significance. I firmly believe that by continuing to explore contemporary art within this context, the Lingnan School of Painting Memorial Hall will provide a balanced reference point for studying the post-Lingnan artistic ecology, ultimately uncovering pathways for Chinese art amidst the collision of Eastern and Western aesthetics.

This aligns with the mission of an academic research institution.

As Professor Zhao Jian, vice president of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, stated in his opening remarks for the exhibition:

The Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Paintings has developed a distinct identity in recent years. It is not a mediocre display venue but a research-oriented memorial hall that explores, organizes, and investigates the artistic and cultural phenomena of “regionalism” — more specifically, the regionalism of southern China. These investigations reflect the natural talent, rebellious spirit, and innovative and revolutionary essence of southern Chinese art.

Regarding “Other Regionality—Youth Experimental Art Exhibition,” I would say that due to the collective efforts of these young artists, the Memorial Hall has achieved a new “state”: either facing the past with extreme dedication or confronting the future with courage. This duality defines the spirit of the Memorial Hall today. For this exhibition, the outcome is of little importance. What matters is the atmosphere it creates and the spirit it embodies, which serve as a declaration.

In this sense, the Lingnan School of Painting Memorial Hall and the young artists have together contributed to a novel and revolutionary interpretation of “regionalism” in southern China.

The first iteration of any project is bound to have shortcomings and limitations, but the “experiment” inherent in this inaugural event is invaluable. After 70 years of New China’s artistic developments, we find fewer genuine experiments, more pseudo-experiments, increasing reliance on technical skill and experience, and diminishing willingness to take risks. Yet, in this exhibition, I see both “experiment” and “adventure.”

This exhibition” offers a new interpretation of the term “regionalism.” This interpretation is connected to China’s current economic status and development. Today, we have the opportunity to define “regionalism” from our own perspectives and values. Thanks to the efforts of the participating artists, this interpretive space is vast. I hope this first edition is not the last and that it evolves into a second, third, and further iterations. I also hope the participating artists will continue to grow, whether in number, diversity, or rotation, as this aligns with the essence of “experimentation” and “another form of regionalism,” as well as the revolutionary spirit established by the predecessors of the Lingnan School.

- This Article in Chinese was first published on Art Journal 2014-04, P90-93

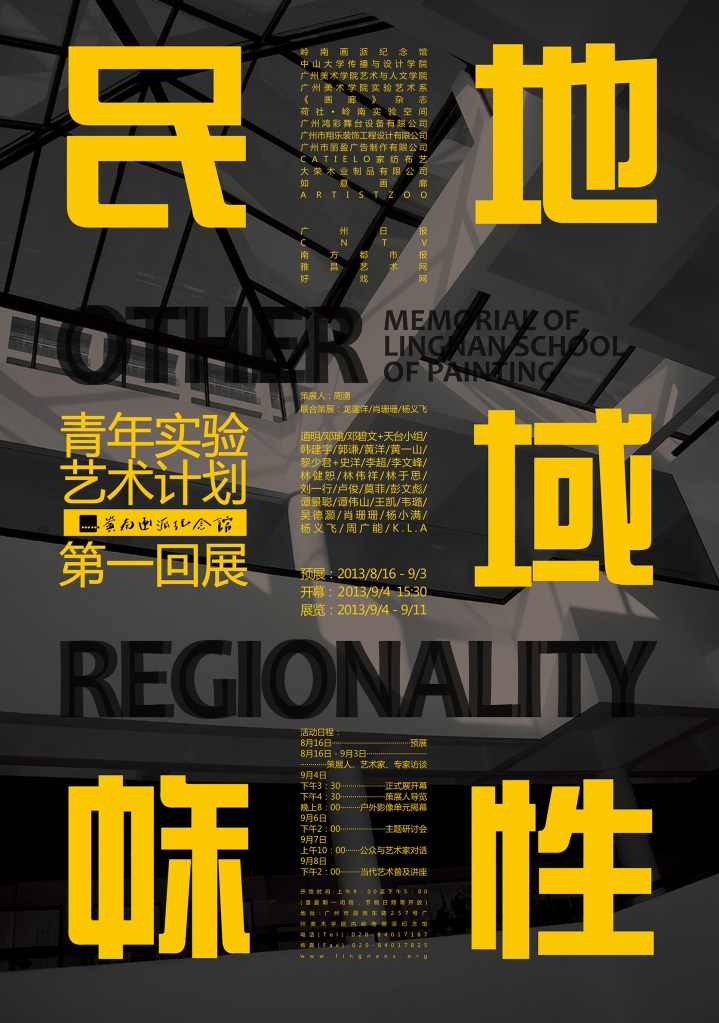

Exhibition poster

Other Regionality

Chief Curator: Zhou Yong

Co-Curators: Steven Dragonn, Xiao Shanshan, Yang Yifei

Artists: Dao Ming, Deng Yu, Deng Biwen+Tiantai collective, Han Jianyu, Guo Qian, Huang Yang, Huang Yishan, Li Shaojun+Shi Yang, Li Chao, Li Wenfeng, Lin Jiansu, Lin Weixiang, Lin Yusi, Liu Yixing, Lu Jun, Mo Fei, Peng Wenbiao, Tan Jingcong, Tan Weishan, Wang Kai, Wei Lu, Wu De Hao, Xiao Shanshan, Yang Xiaoman, Yang Yifei, Zhou Guangneng, K.L.A

Duration: Aug 16 – Sep 11, 2013